Written by Jermaine Magethe

Kenya is rapidly positioning itself as a hub for carbon trading in Africa, promoting carbon credit projects as a pathway to climate finance, conservation, and economic growth. These projects, which turn forests, grasslands, and rangelands into tradable carbon assets, are increasingly being framed as a win for both the planet and development.

What Are Carbon Credits and Why Kenya Is Investing in Them

Carbon credits allow companies or governments to offset their greenhouse gas emissions by financing projects that reduce or absorb carbon elsewhere. In Kenya, this includes forest conservation, soil carbon projects, and changes to grazing or land-use practices.

According to the government, carbon trading could generate billions in climate finance over the coming decades. In response to growing scrutiny, Kenya enacted new carbon market regulations in 2024, requiring community consent, benefit-sharing agreements, and state oversight.

But many carbon projects were approved or negotiated before these safeguards existed, leaving communities and children operating in legal and protection gaps.

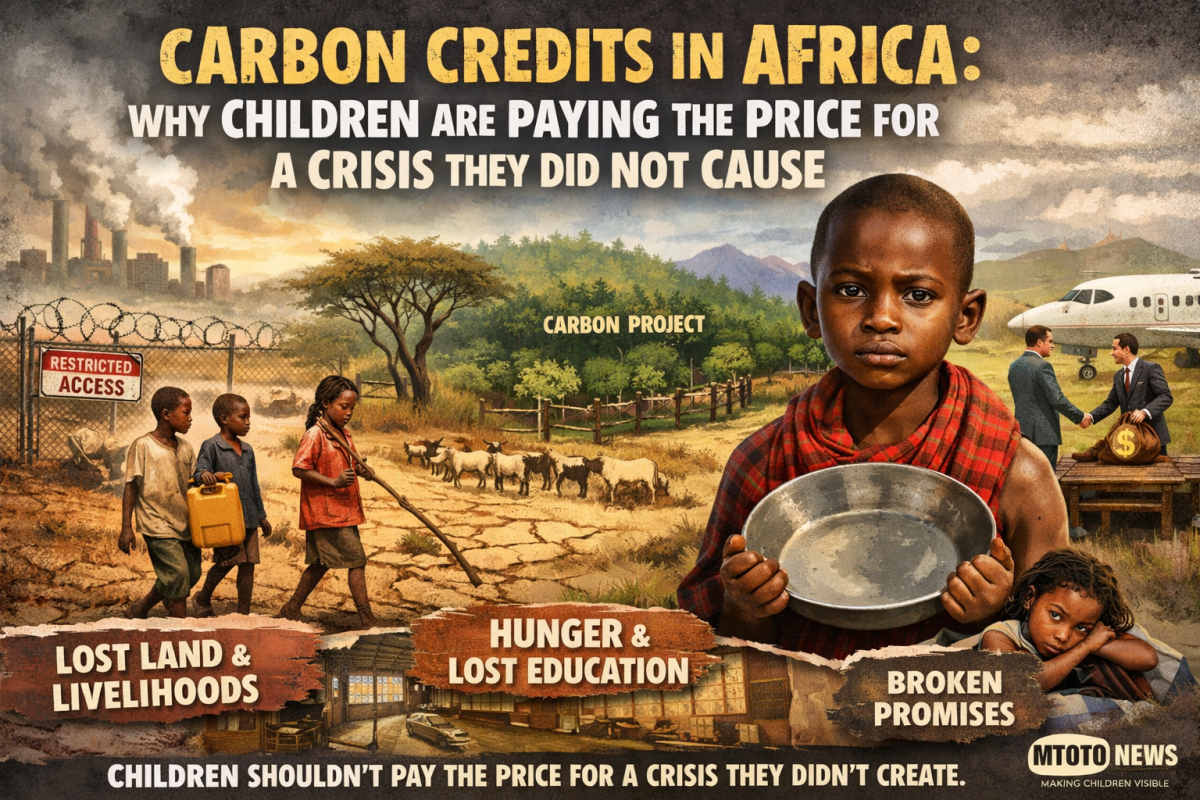

How Carbon Projects Affect Children

Children experience the impacts of carbon credit projects not through policy documents, but through changes to daily life.

- Food security, when livestock mobility is limited

- Education, when children must spend more time herding or fetching water

- Cultural identity, when access to sacred sites, medicinal plants, and traditional learning spaces is blocked

- Safety and wellbeing, as longer distances expose children to increased risks

Yet child-specific impact assessments are rarely conducted, despite Kenya’s obligations under the Constitution, the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, and the African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child.

Land, Consent, and Legal Gaps

This creates tension when carbon developers require formal documentation to prove ownership and consent. Communities may be asked to sign contracts for land that has sustained them for generations, but is not recognised by statutory law.

As policy researchers at Power Shift Africa and the Africa Policy Research Institute have warned, this mismatch creates conditions where communities can be excluded from decision-making, even when their livelihoods depend on the land in question.

For children, the consequences are profound. When customary land is rendered invisible in legal systems, the rights attached to it food, culture, education, and protection are also sidelined.

Transparency and the Risk of Exploitation

Civil society organisations and investigative journalists have raised concerns about the integrity of some carbon projects in Kenya. These include:

- Opaque contracts that communities struggle to understand

- Unequal power dynamics between developers, government actors, and local residents

- “Phantom credits”, where claimed emissions reductions are difficult to verify

- Benefit-sharing mechanisms that fail to reach households or support child wellbeing

A 2025 investigation by DW documented cases in Kajiado County where landowners reported pressure to sign carbon agreements, confusion over terms, and disappointment when promised benefits did not materialise. Similar concerns have been raised by Indigenous communities whose ancestral lands have been linked to conservation or carbon initiatives without their meaningful consent.

Climate Finance or Climate Injustice?

Africa accounts for less than 4% of global greenhouse gas emissions, yet it is among the regions most affected by climate shocks, including droughts, floods, and food insecurity. At the same time, climate finance for adaptation continues to fall far short of what is needed.

Critics argue that poorly regulated carbon markets risk deepening this injustice by allowing wealthier countries and corporations to continue emitting, while shifting responsibility onto communities already facing climate vulnerability.

For children, this imbalance is not theoretical. It shapes access to land, livelihoods, and cultural continuity all essential to healthy development.

Kenya’s updated carbon regulations present an opportunity to address these concerns, but only if implemented effectively. Child-responsive climate governance requires:

- Genuine community consent that reflects children’s needs and futures

- Transparent benefit-sharing that supports education, nutrition, and protection

- Independent monitoring of carbon projects and claimed emissions reductions

- Recognition of customary and Indigenous land rights

As climate policies evolve, children must be recognised not as passive beneficiaries of climate action, but as rights holders whose lives are directly shaped by land and environmental decisions.

Climate action is urgent. But solutions that overlook children risk reproducing the same extractive dynamics that have long defined global inequality this time under the banner of sustainability.

If carbon markets are to contribute meaningfully to climate action, they must do so without sacrificing children’s rights, dignity, and futures

At Mtoto News, we believe that making children visible in climate conversations is not optional.