Written by Jermaine Magethe

“Why are they dancing, Jermaine? Isn’t it a funeral?”

My little brother asked the question quietly, eyes fixed on the television.

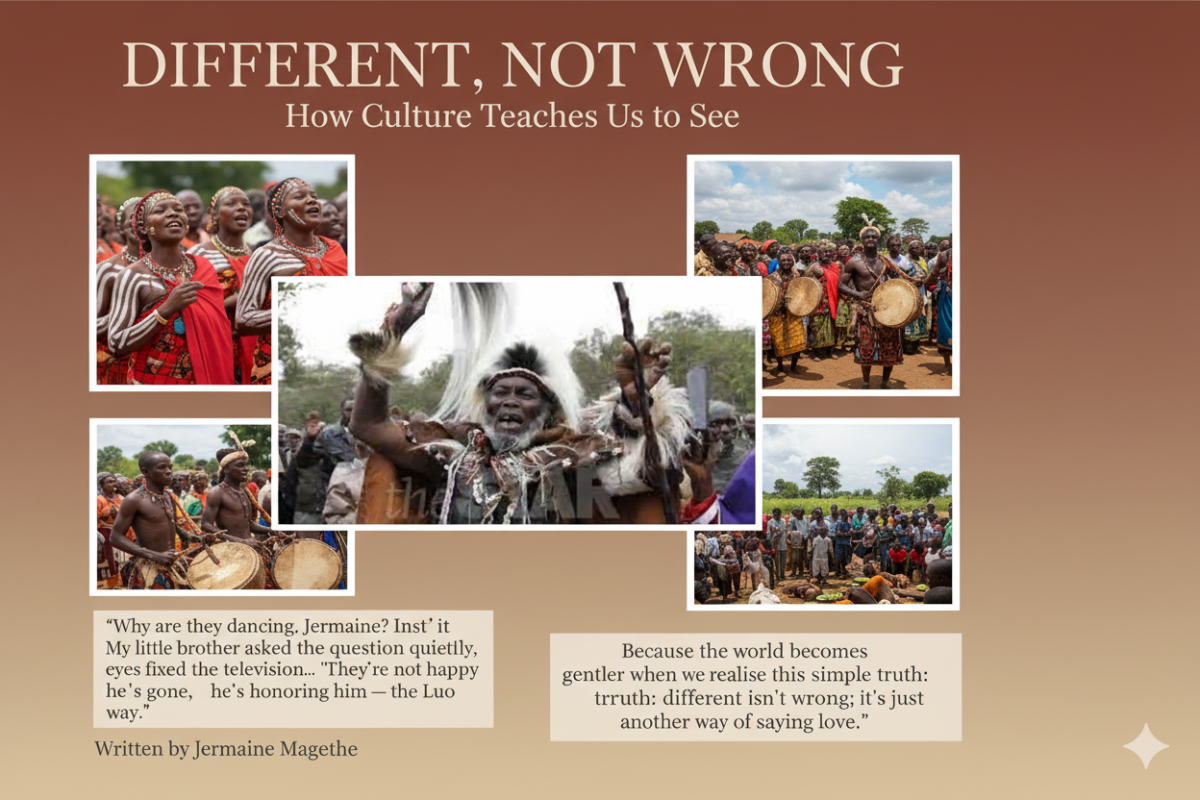

The screen was filled with song, colour, and movement from Raila Odinga’s burial in Bondo, Siaya County; mourners singing, drumming, and celebrating. To him, it didn’t look like a loss. It looked like a festival.

He turned to me, confused. “People are happy… but someone died.”

I smiled, unsure how to answer right away.

“They’re not happy that he’s gone,” I said slowly. “They’re honouring him — the Luo way.”

In Luo culture, death isn’t the end. It’s a return home to the ancestors, to memory, to the stories that never die. The body rests within the homestead, surrounded by songs and stories.

Cows are slaughtered, drums beat through the night, and women ululate not to celebrate death, but to remind life that it still has power.

For the Luo, mourning is a community act. You do not cry alone. You do not suffer in silence.

The songs, the rituals, the gathering are all ways of saying, we were here together, and we will not forget.

My brother looked at me again.

“But why don’t we do that?” he asked.

“Because every community has its own way,” I replied. “Some of us pray quietly. Some sing loudly. Some dance to chase grief away. But in the end, we’re all saying the same thing goodbye, with love.”

He nodded slowly, thinking. “So… they’re not wrong?”

“No,” I said. “Just different.”

That small conversation stayed with me.

Because what my brother asked in his innocent way is something adults often forget: that there is no single way to be human.

Across Kenya, the difference is our shared language.

A Kikuyu family might hold a silent prayer meeting.

A Swahili family might read the Qur’an and cook together.

A Maasai community might dance for days in the open air.

A Luhya home might be filled with song and the laughter of relatives reuniting.

Each act may look unlike the other but each one is stitched with love, memory, and meaning.

Yet somewhere along the way, we learn to treat difference as discomfort.

We hear children giggle at a name they can’t pronounce, or adults whisper about a custom they don’t understand.

“That’s not how we do it,” they say as though every way but theirs is less.

But culture isn’t a competition. It’s a compass.

Each community finds direction in what helps them make sense of life, birth, love, death, and everything in between. That’s what cultural relativism is about not a fancy theory, but a simple act of empathy: the ability to say *I may not understand this yet, but I respect that it means something to you.

If we teach children to look with curiosity instead of judgment, they’ll grow into adults who listen before laughing, who ask before assuming. They’ll see that understanding another culture doesn’t erase your own; it expands your heart until there’s room for everyone’s story.

Maybe that’s the lesson my brother was giving me that day that compassion often begins with a question.

So the next time a child asks,

“Why do they cry like that?”

“Why do they bury people at home?”

“Why do they sing when someone dies?”

Don’t hush them. Don’t say, That’s just how they are.

Say, Let’s find out together.

Because the world becomes gentler when we realise this simple truth: different isn’t wrong; it’s just another way of saying love.