Written by Jermaine Magethe

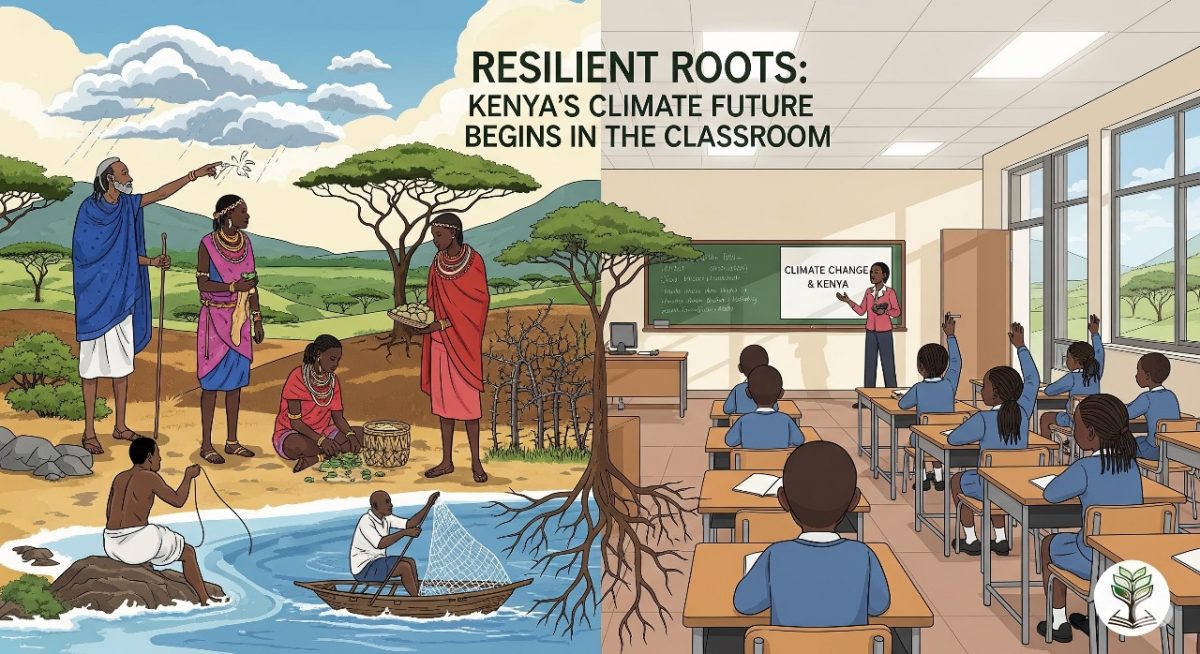

As Africa prepares for the Africa Climate Summit 2025 in Addis Ababa from 8th –10th September , the message from the World Economic Forum in Davos still rings true. There, Indigenous leaders told presidents and CEOs what the world has been slow to hear: Indigenous knowledge is not nostalgia. It is survival technology.

In Kenya, that technology is written in the land and stored in memory.

- Kikuyu elders know the flowering of the mugumo tree means the rains are near.

- Maasai herders rotate their cattle with the precision of climate scientists, preventing land degradation.

- Samburu and Borana communities observe animal behaviour from goat intestine structure to insect presence to predict rainfall and other climate events.

- Mijikenda custodians guard the sacred kaya forests: living seed banks, rainmakers, and biodiversity sanctuaries.

- Afar pastoralists read the wind, classifying six distinct types by timing, direction, and force, using them to forecast weather patterns.

This is environmental science, tested over centuries, and validated by lived experience. But it is slipping away.

When our children never hear these stories, they lose more than culture. They lose a climate survival kit. And when our schools dismiss Indigenous knowledge as “folklore,” we erase a knowledge base that could help them navigate droughts, floods, and shifting seasons.

Kenya is already feeling the heat, literally. Unpredictable floods are sweeping through Budalang’i. Maize crops are withering in Kitui. Rising seas threaten Lamu’s heritage and livelihoods. These are not distant threats. They are today’s headlines.

We need to weave Indigenous climate wisdom into the national curriculum not as an optional extra, but as a core part of science and environmental studies.

Picture this:

- A Grade 4 weather lesson that pairs meteorological data with Kikuyu seasonal indicators.

- Maasai pupils mapping grazing cycles with GPS to understand sustainable land use.

- Coastal students document kaya forest biodiversity in both Kiswahili and Giriama.

This isn’t about replacing modern science. It’s about validating and strengthening it with the precision, observation, and adaptability that have kept our communities alive for generations.

Davos made it clear: the world needs Indigenous knowledge to survive climate change. Kenya has it in abundance. But if we do not act, we risk losing it before our children can inherit it.

The Ministry of Education, curriculum developers, and county governments have a choice: continue teaching climate science in a way that ignores local expertise or build a generation that can read both a satellite map and the signs in the wind.

If we want a safe climate future for our children, we must make them not just students, but stewards. The roots are there. We only have to pass them on.

Kenya’s Indigenous Climate Indicators

Science tested over centuries, rooted in observation

- Kikuyu – Flowering of the mugumo tree signals rain is near.

- Maasai – Rotational grazing patterns prevent overuse and keep grasslands resilient.

- Samburu & Borana – Goat intestine patterns, insect activity, and animal sleeping habits predict rainfall.

- Mijikenda – Sacred kaya forests act as biodiversity banks and influence rainfall.

- Afar – Six distinct wind types, identified by timing, direction, and force, forecast seasonal weather.

- Turkana – Fish migration patterns in Lake Turkana and changes in water bird nesting indicate water level shifts and seasonal changes.

- Pokot – Changes in the color of certain grass species indicate impending drought.

- Taita – Early blooming of mwarubaine (neem) trees signals abnormal seasonal shifts.

- Kamba – Unusual flowering of the mutula tree and termite swarms forewarn of heavy rains.

- Luo – Movement patterns of certain fish in Lake Victoria, coupled with frog calls, indicate approaching storms.

- Meru – Direction and frequency of Mount Kenya’s cloud cover in late afternoons signals the likelihood of next-day rainfall.

Why it matters: These indicators often align with and can validate scientific climate models, offering communities an added layer of predictive power for farming, grazing, and disaster preparedness.